The EEGLAB News #1

Arnaud (aka Arno) Delorme, Ph.D.

Arnaud (aka Arno) Delorme, Ph.D.

Project Scientist and Chief Software Architect of EEGLAB,

Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience (SCCN), UC San Diego

Expert on the neuro-correlates of conscious experience, and co-creator of the open source EEGLAB software

Dr. Arnaud (aka Arno) Delorme remembers thinking, as a 12-year-old in the courtyard of his school in the suburbs of Paris, France, “I need to figure out why I’m here.” To answer that question, he realized he would have to study the brain. He explains, “That was my existential moment in seventh grade where I decided that’s what I want to do, I want to study the brain. And that’s why I’m here.” Arnaud Delorme’s journey has taken him from his home in France, to the U.S., to India six times, and to workshops and events worldwide.

BECOMING A BRAIN SCIENTIST

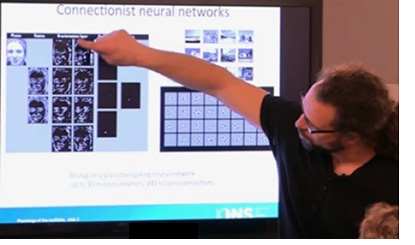

Arnaud Delorme set his path early and has never wavered. He received his Master’s degree in biology and computer science at Paris University, and then earned his Ph.D. in Computational Neuroscience (in 2000) from Paul Sabatier University in France, where he studied connectionist neural networks (for example, studying how neural networks learn to recognize images). The biggest neural network he simulated was 30 million neurons and 245 billion connections!

Arnaud Delorme set his path early and has never wavered. He received his Master’s degree in biology and computer science at Paris University, and then earned his Ph.D. in Computational Neuroscience (in 2000) from Paul Sabatier University in France, where he studied connectionist neural networks (for example, studying how neural networks learn to recognize images). The biggest neural network he simulated was 30 million neurons and 245 billion connections!

That same year, he took a postdoctoral position at the Salk Institute in the laboratory of Terry Sejnowski’s (Director of the Computational Neurobiology Laboratory at The Salk Institute, and Director of the Institute for Neural Computation at UC San Diego). He later became a principal investigator in Toulouse, France in 2005.

THE BEGINNING OF EEGLAB

THE BEGINNING OF EEGLAB

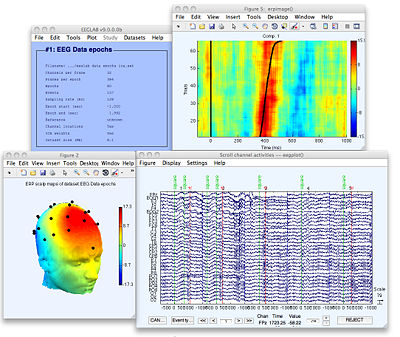

It was here, in Sejnowski’s lab, where the EEGLAB was born. There, Delorme met scientists Scott Makeig and Tzyy-Ping (TP) Jung. He had yet to analyze the electro-encephalography (EEG) data from his thesis on visual psychophysics. Fortunately, Delorme recalls, “Scott and Tzyy-Ping had developed functions in Matlab to process some of the data, and I started using these. I develop my own function for rejecting artifacts. Then, in around 2001, I decided to build a graphic interface for these functions, to make it more usable.”

The use of EEG at the Salk Institute grew so quickly, that a new lab called the Swartz Center for Neural Computation (SCCN), and selected Scott Makeig as its Director. In about 2010, SCCN moved to the Institute for Neural Computation, located in the San Diego Supercomputer Center at UC San Diego. Once at the new location, Delorme worked fervently to make the Matlab script and graphic interface more reliable.

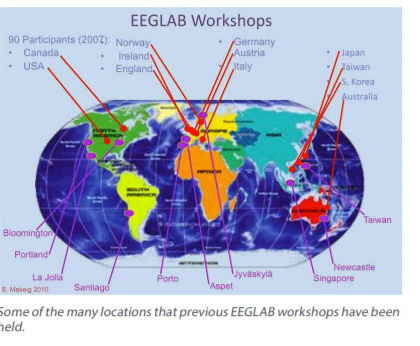

The first real version of this Matlab toolbox for EEG analysis, which they called EEGLAB, was revealed in 2003. It was a team effort between Scott Makeig, and Arnaud Delorme.“ We had our first EEGLAB workshop in 2004 at the San Diego Supercomputer Center,” Delorme states. “Where we are now, that’s where we started.”

EEGLAB found immediate popularity, due, in part, to timing. It was the only open source tool available at the time, in a field filled with expensive commercial software that was often not as complex or robust. EEGLAB offered powerful tools that helped analyze EEG data, such as artifact removal (removing signals that don’t originate from the brain) and independent components analysis (ICA -- separating signals that are mixing together). And a huge benefit was its ease of use. People could select menus through the graphic interface, without having to learn a programming language, and their input automatically created Matlab scripts – scripts that Delorme says “are immensely more powerful than anything a commercial company can do.“

From its inception, EEGLAB usage quickly grew. Thousands of researchers began using EEGLAB to analyze their EEG data, and the group compiled an email list comprised of scientists worldwide. To date, the EEGLAB reference paper has over 10,000 citations (5.4 citations a day!), and this year the software has been downloaded around 2,500 times per month. Currently there are 6,571 opt-in researchers on the EEGLAB discussion mailing list, and 15,235 researchers on the EEGLAB news list, anticipating updates to the code. The program never stops growing and transforming. Users can suggest changes, make bug fixes, and add new functionalities with their own contributions to the code. Currently, over 100 plug-in toolboxes for EEGLAB, contributed by labs all over the world, are freely available through the online EEGLAB Extension Manager.

From its inception, EEGLAB usage quickly grew. Thousands of researchers began using EEGLAB to analyze their EEG data, and the group compiled an email list comprised of scientists worldwide. To date, the EEGLAB reference paper has over 10,000 citations (5.4 citations a day!), and this year the software has been downloaded around 2,500 times per month. Currently there are 6,571 opt-in researchers on the EEGLAB discussion mailing list, and 15,235 researchers on the EEGLAB news list, anticipating updates to the code. The program never stops growing and transforming. Users can suggest changes, make bug fixes, and add new functionalities with their own contributions to the code. Currently, over 100 plug-in toolboxes for EEGLAB, contributed by labs all over the world, are freely available through the online EEGLAB Extension Manager.

In addition, several EEGLAB workshops occur each year, held throughout the world. In 2017, workshops were held in Mysore, India, Tokyo, and Be’er Sheva, Israel. In 2018, they were held in Pittsburgh and San Diego.

Dr. Delorme envisions EEGLAB becoming even more robust in the future. He would like to see more brain connectivity analysis, EEG data mining using super-computers, more statistics, and additional collaborations with other researchers to develop new tools

MEDITATION, MIND WANDERING, AND CONSCIOUSNESS

Even with his success studying neural networks and his efforts to improve EEGLAB, Dr. Delorme felt an inner stirring to push on -- to delve deeper into the scientific study of consciousness. “What do we know about consciousness?” he asks. “Studying neural networks and neural recognition of objects is serious brain hacking, but it is not really studying consciousness. For instance, in the standard neuroscience model, consciousness is supposed to emerge from neural networks activity. Yes, the process by which subjectivity emerge from neural networks is both unknown and magical. Maybe we have it all wrong. Science can tell me HOW things work, but it does not explain WHY.”

Even with his success studying neural networks and his efforts to improve EEGLAB, Dr. Delorme felt an inner stirring to push on -- to delve deeper into the scientific study of consciousness. “What do we know about consciousness?” he asks. “Studying neural networks and neural recognition of objects is serious brain hacking, but it is not really studying consciousness. For instance, in the standard neuroscience model, consciousness is supposed to emerge from neural networks activity. Yes, the process by which subjectivity emerge from neural networks is both unknown and magical. Maybe we have it all wrong. Science can tell me HOW things work, but it does not explain WHY.”

So Dr. Delorme started to explore Eastern philosophy, became a Zen meditator, and began scientifically studying meditation. His path led him to India six times – teaching, collecting data from meditators, and performing research on meditation and consciousness.

During his first trip to India in 2003, he taught a class, the Neuroscience of Consciousness, at the Birla Institute of Technology in Delhi. “I was teaching neural correlates of consciousness – what happens in the brain when we are conscious,” he shares. Delorme later returned to Rishikesh, India, to the Meditation Research Institute, “where they had a very extensive piece of EEG equipment and they didn’t know what to do with it. We wrote up a small grant and performed studies for four years – collecting data from 150 meditators of different (meditation) traditions.”

There are many types of meditation, and what’s true for one meditation may not be true for another type. “So,” Delorme explains, “we recorded people using four different meditation traditions and compared them with a control group. We also recorded their heart rate, skin conductance, and emotional reactivity. We found that all four types of meditation had some commonalities (and differences from the control). For example, they tended to have more high range frequencies (gamma frequencies) distributed all over the brain, which is consistent with other studies.”

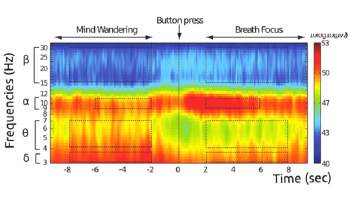

Dr. Delorme also began running experiments to track brain dynamics during meditation and mind-wandering. He looked at scalp topography, brain frequencies, and structural brain changes such as thickening of the cortex, using fMRI. While he is still in the process of analyzing the data, his data suggests the presence of different brain frequencies when our minds wander compared with when they are focused.

Dr. Delorme also began running experiments to track brain dynamics during meditation and mind-wandering. He looked at scalp topography, brain frequencies, and structural brain changes such as thickening of the cortex, using fMRI. While he is still in the process of analyzing the data, his data suggests the presence of different brain frequencies when our minds wander compared with when they are focused.

Image (to left): Scalp topography - red means high amplitude brain waves, green means low amplitude brain waves, and yellow means intermediate amplitude brain waves

MEDITATION AND NEUROFEEDBACK

Over the last decade, there has been a huge increase in meditation research. “When I first started studying meditation, it was a taboo subject – something that could end a career. But now it is very mainstream,” Delorme admits. This is due, in part, to improvements in neuroimaging methods, and to the view that meditation could be used as a therapy to improve health.

Over the last decade, there has been a huge increase in meditation research. “When I first started studying meditation, it was a taboo subject – something that could end a career. But now it is very mainstream,” Delorme admits. This is due, in part, to improvements in neuroimaging methods, and to the view that meditation could be used as a therapy to improve health.

Delorme feels a need to expand meditation research to look at more than stress reduction. He helped organize The Future of Meditation Research Project, a consortium of scientists who plan to look beyond “meditation for stress reduction” and towards meditation and its effects on other aspects of our lives.

With the possibility of seeing real benefits to meditation, Delorme has become interested in meditation and neurofeedback. He wants to determine whether neurofeedback (a form of biofeedback in which subjects respond to a display of their own brainwaves to teach self-regulation) can help individuals develop their meditation practice more rapidly and reduce mind-wandering. He explains, “I am most interested in looking at the spiritual experience people have, and wellness, and neural correlates of happiness. Of course, first we have to determine what type of happiness we are talking about. There are neural correlates to different emotional states (such as compassion or equanimity). Once we identify these markers of happiness, the goal eventually is to use neurofeedback to train people to down regulate their EEG, and ultimately, to be HAPPIER.

MORE QUESTIONS

MORE QUESTIONS

As if his “plate” isn’t full enough, Dr. Delorme is eager to investigate other enticing questions about consciousness – for instance, about mediumship: “Is there such a thing as global consciousness that a medium can have access to?” He would also like to study deep learning and EEG, to investigate timely questions such as, “Will we ultimately be able to read the thoughts of people?” For which he pauses and then responds, “I don’t know if we have enough information to view that through an EEG. With Intracranial EEG, using enough channels, I have no doubt we can do that in the future.”

Circling back to his life goal, Dr. Delorme concludes: “Ultimately, I would like to answer the question – What is the nature of consciousness? Is consciousness local to the brain – does it need a brain? Or can machines and other objects become conscious?” All along, Delorme’s plan has been to use the scientific method to answer this question. “Science is just a method. My goal is to use the tools of science, along with the best statistics I know, to show whether global consciousness exists or not. We are very lucky we live in an era where we have the technology to study these questions.” His 12-year-old self would heartily agree.

R. Weistrop, June 2019